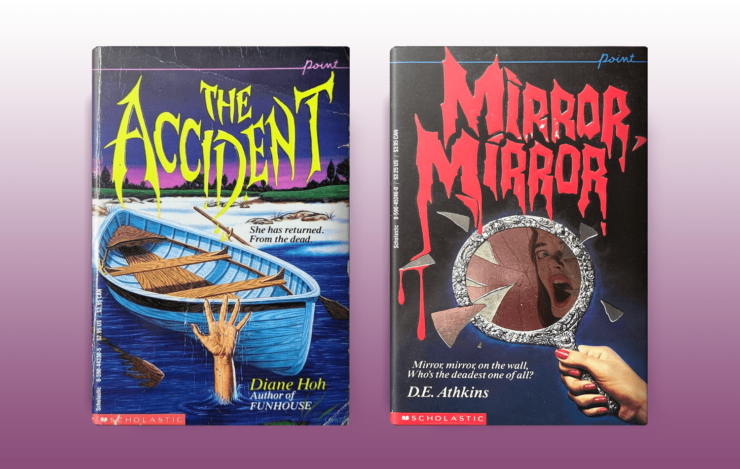

Mirrors in the horror genre can be pretty terrifying and not just in a “yikes, bad hair day” kind of way. They can plunge us into the realm of the uncanny where what we see is simultaneously recognizable and unfamiliar. They can act as thin spots between realities, fluid and permeable when they’re supposed to be solid and reliable. They can show us things that are meant to remain invisible, reflections of people or things that shouldn’t be there, that aren’t there in “real life,” like a figure just over the shoulder of our reflection or a different face lurking just beneath our own. In Diane Hoh’s The Accident (1991) and D.E. Athkins’ Mirror, Mirror (1992), mirrors are central to the horrors encountered by their protagonists, ranging from past trauma to the price of beauty.

In The Accident, Megan Logan and her family have recently moved into a lake house that was left to them by Megan’s grandmother, Martha. Megan’s life is pretty good: she has a lot of friends, loving relationships with her parents and younger brother Thomas, and a crush on a guy named Justin, though she’s too shy to ask him to her birthday party (she’s working on it). Then things get complicated: shortly after three of her friends are in a terrible car accident, a voice starts talking to Megan from the mirror in her bedroom, starting with “Why are you crying, Megan Logan?” (14). Megan actually takes this pretty well in stride—all “who are you?” rather than “is this an auditory hallucination?”—and she quickly establishes conversation and rapport with Juliet, the girl in the mirror, who appears as a diffuse purple-y shadow in the glass. Grandma Martha’s mantra had been “Believe in everything, until you learn otherwise” (39) and this is advice that serves Megan well as she begins interacting with Juliet.

Juliet tells Megan that she died by drowning in the lake when she was fifteen years old in 1930 and has been desperately waiting ever since to tell her story. As Juliet explains, “I can’t talk to just anyone. Has to be someone exactly my age. Someone near the lake, where I died. Someone with an open mind and a kind heart. Someone with imagination and a belief that anything’s possible. Someone just like you, Megan Logan” (34). And with this plea for empathy and connection, Juliet’s hook is set, because obviously, talking to Megan isn’t all she wants to do: she wants Megan to trade places with her for a week so Juliet can live the life she was denied, after which she promises she’ll swap back with Megan, be at peace, and cross over into the hereafter. When Megan hesitates, Juliet ratchets up the manipulation with guilt (Megan has her whole life and all Juliet wants is one little week, so it would be selfish to say no), immediacy (it’ll only work as long as they’re the same age and Megan’s sixteenth birthday is in a little over a week, so it’s gotta be now), and fear (her friends’ accident wasn’t an accident, someone might try to hurt Megan next, and Juliet’s much better at detecting evil threats than Megan is, so Megan will really be safer if she just gives up her identity in the corporeal world). Of course, Megan agrees, because she’s sweet and she’s kind of a pushover and it would be a really short, boring book if she didn’t. But she does make Juliet promise to ask Justin to be Megan’s date for her birthday party, so she’s not walking away empty-handed.

Buy the Book

The Book Eaters

Juliet adjusts to the late 20th century remarkably well for a girl from 1930. She wears a lot of makeup and she loves hanging out at the mall and making out with Justin, adding an erotically charged component to Justin and Megan’s relationship that wasn’t there before. Megan begins by worrying that all this smooching is going to give the game away if Justin catches on that this isn’t really Megan, though her concern quickly morphs when she realizes that Justin doesn’t seem to mind this new development at all and she instead begins to worry that he might like Juliet-Megan better than he likes Megan herself.

While Juliet is upending Megan’s life by being rude to her family, sneaking out at night, buying sexy dresses, and making salon appointments to get Megan a new look, horrible things keep happening to Megan’s family and friends. Before she swapped places with Juliet, Megan’s friends Jenny, Barb, and Cappie were in a car accident caused by someone maliciously tampering with their steering and Hilary was pushed off the catwalk above the school’s theater stage. After Megan and Juliet make the exchange, someone hits Megan’s mom in the back of the head and tosses her into the lake to drown, her brother gets hit by a truck while riding his bike, and her dad falls off a ladder and breaks a plate glass window, all while Megan is getting cryptic and creepy crayon drawings telling her who’s going to be next.

Megan is desperate to get out of the mirror so she can take back her life and protect her family and friends but, unsurprisingly, once the deal is done, it doesn’t work quite the way Juliet promised it would and Juliet refuses to give Megan’s body up. Megan’s experience of life in the mirror also isn’t anything like Juliet said it would be and instead of a peaceful, disembodied sense of cocooned weightlessness, “the blackness in which she found herself was unrelieved and icy cold” (64), imposing an insurmountable distance and isolation that leaves her a spectator to her own life. Juliet’s refusal also re-grounds the horror in the mirror, the house, and Megan’s family history, when Juliet reveals that she was Megan’s grandmother Martha’s stepsister and accuses Martha of murdering her, saying that she could have saved Juliet from drowning and actively chose not to (a claim that remains remarkably unresolved). Martha’s house and its possessions – particularly the mirror in Megan’s room – serve as a kind of conduit between these two periods, holding Juliet and her unresolved desire for vengeance, though this correlation becomes a bit complicated when we learn that (of course) Juliet is responsible for all of the bad things that have been happening, able to invisibly leave both the mirror and Megan’s body to put her malicious plans in motion.

While the mirror establishes this connection to the past and is an effective medium for highlighting the contrasts between Megan and Juliet-Megan, it is another kind of reflection that is needed to put things back the way they’re supposed to be before the clock strikes midnight, when Juliet will take permanent residence in Megan’s body and Megan will cease to exist. The only way to boot Juliet out of Megan’s body is for Juliet to vacate it of her own free will and the only way to do that is by physically reenacting Juliet’s death and basically murdering her out of Megan’s body. It turns out that Justin can hear disembodied Megan if she tries hard enough, because their bond is pure and he really wasn’t all that into sexy Juliet-Megan (more on this in a bit), and he’s happy to help Megan, coercing Juliet into a boat that she repeatedly tells him she doesn’t want to get into, heading toward the cove where she died despite her increasingly panicked protests, and forcing her to reenact her death. Juliet is definitely awful, and this is clearly established as the only way for Megan to get back into her own body, but this is still clearly shown to be brutal and traumatic, as Juliet finally gives up Megan’s body with “a bellow of rage so despairing, so filled with anguish and torment, every creature within hearing distance shivered with fear. Animals hid in burrows and tree branches and bramble bushes, and people in their houses on the lake slid deeper beneath their bed coverings, taking refuge from the obscene sound” (164). Juliet remains an ephemeral presence as “the echo of a despairing, tortured wail in the soft whisper of the wind” (165) and we never find out whether or not there was any legitimacy to Juliet’s claim that Martha was responsible for her death (unless we take the book’s title as our definitive answer), but everyone’s back on the right side of the mirror, everyone who has been hurt is on the mend, and most importantly, Megan’s sixteenth birthday party is back on for the next day, so all’s well that ends well(ish).

While the mirror in Hoh’s The Accident takes Megan out of herself and connects her to the past, in D.E. Athkins’ Mirror, Mirror, the proliferation of mirrors take Dore Grey deeper and deeper into herself, as she tests the limits of what she’s willing to do to capitalize on and exploit her beauty. Dore (short for Dorothy) measures her self-worth by her beauty, a validation that has been passed down to her and is continually reinforced by her mother. As Dore reflects early in the novel, “She was beautiful. She had known it for so long that in some ways, she took it for granted. Didn’t even see it when she looked in the mirror. Looked only for, worked only with, the flaws that marred what other people said was her gorgeous face … She had been working at being beautiful, more and more beautiful, ever since she could remember” (5). Dore fixates on her physical appearance, works out obsessively, and constantly questions her looks and her self-worth. One wall of her bedroom is entirely lined with mirrors, making this consideration of and fixation on her body, face, and beauty unavoidable for Dore, and this obsession becomes even more pronounced when her new friend Luci gives her an ornate, antique hand mirror.

Just as Megan’s behavior changes when Juliet takes over, once Dore falls under the thrall of Luci’s mirror, she becomes a different person. Dore throws over her sweet, if goofy, boyfriend Stan to start having steamy hookups with random guys, and while her friendship with Gwen was previously rock solid, after the mirror, she abandons drunk Gwen at a party without a care for what might happen to her. Dore’s abandonment of Gwen is particularly significant because Gwen serves as a counterpoint to Luci’s influence, as not just one of Dore’s dearest and kindest friends, but also a “rescuer of stray cats, rabid advocate of animal rights, [and] hard-core vegetarian” (3), a force of empathy and good in Dore’s world. Dore gives herself over to a life of narcissistic self-satisfaction and hedonism, enjoying champagne and caviar with Luci, sabotaging her friends, publicly humiliating her rivals, and seducing other girls’ boyfriends for fun and self-validation. When Luci tells Dore about an audition for an upcoming feature film that could be Dore’s big break and get her out of her small town forever, Dore is willing to sacrifice anything and anyone to get her chance.

As Dore slides down this slippery slope, the mirror begins to show her increasingly monstrous versions of herself and by the end, when she looks in the mirror she sees “a creature so hideous that Dore couldn’t look away … The lipless mouth opened, taking its own evil breath. Foul, uneven teeth showed beneath it, and a bulbous tongue flickered out like a snake’s and ran across where the lips should have been” (120). Much like The Picture f Dorian Grey, whose name Dore’s invokes, Dore’s physical form remains unchanged while her reflection shows the influence of evil and corruption on her soul, visible only to her as she gazes upon her now-tainted reflection. From the outside looking in, Dore is as beautiful as she has always been, but the mirror shows her this other perspective of herself, someone who is willing to hurt other people to get what she wants, including her boyfriend, her best friend, her parents, and any other young woman who Dore happens to view as competition or a threat to the supremacy of her beauty.

The mirror in Mirror, Mirror is a ‘90s teen horror variation on the age-old Faustian bargain, as Luci is short for Lucinda, who turns out to be a variation of Lucifer, and Dore discovers that she has made a deal with the devil. The recurring theme of apples also calls to mind Snow White, the evil queen’s obsession with being “the fairest of them all,” and the lengths she’s willing to go to to hold on to that distinction. After having sacrificed every relationship in her life for beauty and a chance at fame, Dore is lured onward by Luci, into the intersection of a busy street, where Dore is hit by a car, maimed and mangled as she is dragged beneath it, losing everything she had sacrificed so much to secure. When Dore wakes up in the hospital, she discovers that there never was any audition and Luci has vanished without a trace. When she looks in the hospital mirror, she sees her face “puckered and twisted with scars. Hideous. A monster was looking back at her” (127). The doctors and her parents promise her the best specialists and plastic surgeons, reemphasizing the importance of the beauty Dore has lost, while simultaneously telling her she should be grateful that she survived at all. When Dore is left alone, she picks up Luci’s mirror once again to see “The most beautiful girl in the world … looking back at her” (129) before descending into mad laughter. Dore has survived, but she has not been redeemed or saved, as Mirror, Mirror ends on a darkly existential and hopeless note.

The Accident and Mirror, Mirror are preoccupied with beauty and physical appearance, both in how the protagonists see themselves and in how others perceive them. Interestingly, both novels also make an overt comparison between beauty and sex appeal, through overtly sexualized female characters (what in Fear Street parlance, we might call the Suki Thomas Pheonomenon). In The Accident, Vicky Deems is a stark contrast to Megan and her friends, clad in “a bright red halter top and a black leather miniskirt fitted snugly around her beautiful body” (55) as she leans close to seduce Justin. She is referred to as “Tricky Vicky” (48) and a “Viper Extraordinaire, who always had that cold, hungry look in her eyes” (54). She was suspended for cheating on a test, so her female peers deduce that she must be immoral and unintelligent. She flirts with every guy she bumps into and has an established reputation for being “easy.” When Megan sees Vicky at the lake with boys she doesn’t recognize, her first assumption is that “Vicki must have already conquered the entire male population of Lakeside and been forced to seek out fresh new territory” (72). Vicki is depicted as a femme fatale, but ultimately inconsequential. Other than serving as a sexual threat and a flimsy symbol of licentious immorality, she doesn’t matter: she is sexualized and sensationalized, then dehumanized and dismissed, a comparison by which the “good girls” can establish and reassert their own superiority. In Mirror, Mirror, while Dore is beautiful, Luci is sexy and Dore’s realization of this difference is the catalyst that sets off the deal Dore will eventually make. As she looked at Luci, “Dore, who knew she was a thousand times more gorgeous than this Lucinda, felt plain. Sexless. Boring … She hated it” (21). Dore decides that the only accurate way to describe Luci is as a “vamp” (27), wrestling with the old fashioned-ness of the word, heard from her mother, but sensing its rightness, its position as the one word that captures who Luci is and how Dore feels about her. Luci is sexy but turns out to be the devil in disguise, and while Dore herself becomes increasingly sexy, it’s at the cost of her soul. Sexiness in Mirror, Mirror is a dangerous prospect.

And not only is this sexuality dangerous, it turns out—at least according to these authors – that that’s not really what guys want anyway, or at least not the ones worth having. In Mirror, Mirror, Dore works her way through a string of meaningless hookups who don’t care about her at all, while sweet Stan chooses kind, quiet Gwen (though Gwen also has her own descent into bad behavior, pushed over the edge by Dore’s betrayal). In The Accident, Megan worries that Justin will like the more sexy version of herself that he thinks she is when Juliet’s in control, but while “Most guys would have been wild about the new, livelier, more affectionate, girl he was spending so much time with these days … the truth was, he missed the ‘old’ Megan. The one he could talk to about anything while she listened, and always understood. The Megan who never flirted with other guys, and was nice to people, and cared about her family” (143). Even teenage boys—or at least, the right kind of teenage boys—would rather have the likable good girl than the sexy bad one, which is reassuring for Megan but also problematically reinforces desirable femininity as passive, attentive, and “nice.”

The mirrors in The Accident and Mirror, Mirror clearly show readers how much more there is than meets the eye. Whether it’s the burden of family history or the consequences of an infernal bargain, when Megan and Dore look in the mirror, there is more than their own reflection gazing back at them. Physical beauty is shown to be one of the most important characteristics a young woman can possess, capital that can be used to define her worth among her peers and in the wider world. This beauty is more than skin-deep, however, as Megan’s kindness and Dore’s corruption echo through the reflections depicted in and conflicts surrounding their respective mirrors. Each of these mirrors opens the doors to both authenticity and impossibility. Megan and Dore have gazed into the abyss of their mirrors and in true Nietzschean fashion, the abyss has gazed back into them, as their interactions with what they find there fundamentally shape their sense of who they are, the choices they make, and the paths their lives will take moving forward.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.